Think Week 2021

At the end of October I stayed two weeks in a small town in Bavaria, Germany. I spent those 14 days living the simple life—I read, wrote, and hiked the nearby mountains with my camera.

The trip was inspired by Bill Gates. In 1995, he wrote a historic memo called The Internet Tidal Wave. It analyzed the future of the internet and predicted it would change the way we use computers. That tidal wave is now long gone and others have since swept over us. But the content of the document is not what interests me the most. It is how the document was formed.

Allegedly it was written during one of Bill Gates’s think weeks. A week set aside to think without distractions. Gates would go on these twice a year to disconnect from daily life and work on tough problems.

And so in September 2021 I decided to plan such a trip. Not just one week, but two entire weeks away from everyday distractions. Instead of reading papers 18 hours a day, every day, I would read some days and hike others.

I expected to think about how I can create better videos, go on more adventure trips, learn about AI and minimalism. And I did indeed think about these things. But in the process I discovered much more.

The following is my personal Think Week Memo 2021.

The sender and recipient is myself. But as I have now worked countless hours on this I want to share it with you. Maybe you will find something useful. Maybe not.

Here it goes.

To: Whom It May Concern

From: Me

Date: 1 Dec 2021

The Future of Me Inc

Objectively speaking I have more than I need. I have a place to live and work that pays the bills. I have good health, enough spare time that I’m able to write this, and I never fear for my life.

Subjectively speaking I also feel blessed. I have close friends and a loving family. I have hobbies that interest me and I’m rarely bored. I have a functioning body that does not limit me and only occasionally breaks down with injuries. And last but not least I have a sharp mind that I love to challenge.

My life is good. So why spend time thinking about the future? A valid question as maybe I should just focus on being content with what I already have. But that still relates to the future—I decide to focus on being content now, moving forward. Every moment I have a decision to make: stay here in the present or something else. The future comes no matter what. And all I can do is decide in each moment what to focus on.

That is what this is. Not me thinking about my life in ten years. No five-year plan or end-of-the-year goals. It is me choosing what to focus on right now. And right now. And right now…

What do I want to focus on? For one, I want to maintain the good parts already there. And that doesn’t just happen. I need to work on it. Invest in it. But more than just maintaining status quo I want to grow. I may feel blessed but I still have major issues. All life is a constant struggle so I’ll never fix everything. But I can build myself a bit stronger every day. I want to be better equipped to handle the trials of today and those yet to come.

In the past three years a lot has happened. I started working my first real job and received my first big paycheck. This new income has led to habits I’m not entirely proud of. I buy stuff left and right and I don’t know why. I have worked for more than three years now and I still enjoy most days. But I can also sense changes. In the beginning everything was new and exciting. Now I’m more experienced and that comes with new challenges. At least once I’ve heard myself utter the words “…that’s how we usually do it”. Followed by a wince as I realize what I have become.

I have also taken up new hobbies. Backpacking in particular this last year. I love it but still struggle to get out. It should be so simple—pack a bag and go. But fear has a funny way of distorting the world. Suddenly all these other things seem much more important.

Another new hobby is video creation. It feels like I’ve done it for a while but in reality it has been less than three years. Three years where I have created videos and published some of them. Creating a few minutes of coherent video turned out to be much harder than I expected. And I’m still learning the basics. But I also want to learn beyond these fundamental skills. I want to create videos that do more than just sit on my empty YouTube channel with no viewers.

Life is good. But I believe part of the reason is that I’m excited for the challenges ahead. I should be content with what I have. And I’m working on that. But I also want to see what is possible if I push myself.

After two weeks alone in the small town of Mittenwald1 this is what I have decided to focus on:

Minimalism

Minimalism has been on my radar for a while. At first just as an interesting life philosophy and later as something I actively wanted to try. Most of my minimalism knowledge was from casually watching Matt D’Avella and reading a bit here and there. But minimalism was at the top of my list for this think week.

I finished Goodbye, Things: The New Japanese Minimalism, read a bunch of posts on becomingminimalist, zenhabits, mnmlist, and Medium.

I also experienced minimalism in action. At least I believe so. In Goodbye, Things, Fumio Sasaki uses travel as an example of the freedom that de-cluttering and minimizing can bring. Re-reading that passage resonates with me in a way that is hard to describe—it is so spot on: how I pack all sorts of items in fear that I may need them. Yet I feel nervous that I have forgotten something as I walk out the door. And finally, how I realize none of that matters and I will be okay.

“You set down your bag and step out for a walk around the neighborhood. You feel light on your feet, like you could keep walking forever. You have the freedom to go wherever you want. Time is on your side…” - Goodbye, Things by Fumio Sasaki

Why I’m Interested

This is my attempt at explaining why minimalism makes sense. For me. I’m certain some of my views will change as I learn more but we all have to start somewhere.

Minimalism is about intentionality. Being clear about what matters and then intentionally focusing on that, removing all other distractions. I’ve spent the last two weeks with minimal distractions. I have not read the news, been on social media, or distracted myself in any of the ways I usually do. And I have loved it. I know very well I will not be able to fully replicate this experience in everyday life. I have bills to pay and fears to tend to. But for just a sliver of the experience I believe it is worth trying.

With minimalism we can dream big. Not about a big apartment filled with stuff I don’t use. But about the things that matter to me.

Minimalism can be good for the environment. Climate change is one of the biggest threats facing humanity and spending less on material possessions is likely to be better than a consumer-driven mindset. It is most definitely better than the materialistic tendencies I have right now.

Minimalism is about freedom. Freedom from distractions. Freedom from pretending. It is freedom to move. Freedom to do what I want. E.g., I’m not sure I like my current apartment anymore. But right now I’d rather stay than move as the thought of moving all my stuff is debilitating. My things are weighing me down and taking my energy in a very real way. It is stripping me of the freedom to easily move.

Minimalism acknowledges the cost of each item is nonzero. The items I own take up space. And space isn’t free. But more than just money, my stuff also takes up focus, time, self-worth, and energy. One example where this can be observed is cleaning. Cleaning my apartment takes more time the more stuff I have. And so it consumes my time and my energy. But it also drains my focus and self-worth as I don’t clean as often as I would like. How many of my items are worth their actual cost?

Another cost is anxiety about the future. The more we have, the more we stand to lose. I recently bought a mountain bike. I enjoy riding it but the purchase has also introduced a new fear into my life. I now fear losing my new bike. And this fear is very real. I have considered bike insurance now that I have two bikes to lose. And such insurance is just a way to relieve my fear using money. Does this mean that I should get rid of my MTB? It depends. If the positive value outweighs the negative I should keep it. But too often we never consider all the negative aspects of owning more stuff. Instead we often completely neglect to consider any negative consequences.

Minimalism believes the desire for more is manufactured. It is not natural, the “truth”, or the only way to live and feel. It is something we have built with our current society. Capitalism and Consumerism are what Yuval Noah Harari calls imagined orders. An imagined order is completely made up. A myth we tell ourselves so that we can cooperate and have an effective society.

Consumerism is a social and economic order that encourages the acquisition of goods and services in ever-increasing amounts. With the industrial revolution, but particularly in the 20th century, mass production led to overproduction—the supply of goods would grow beyond consumer demand, and so manufacturers turned to planned obsolescence and advertising to manipulate consumer spending. - Wikipedia

Companies need us to buy more and more. And to get us to do this they tell us that we are not enough. That we need what they sell. But the companies aren’t at fault. At least not all of them. They are doing what they were put in this world to do—make money for shareholders. Not consider what is good for the individual. The myth is that this is good for society as a whole. But with the challenges facing our society today this imagined order sounds less and less appealing.

How I’m Getting Started

A few weeks ago I removed a couple of drawers from my apartment and went through my clothes once. These two actions yielded good results but I feel like progress has been too slow. If I continue like this I may reduce my excess and distractions to a level I’m happy with in a decade or so.

So here is my plan:

- I have booked a weekend for myself to focus entirely on de-cluttering. I hope this initial shock to the system will show me some of the benefits of minimalism and guide me forward. My biggest concern with this is that I know getting rid of things is difficult. It is a process and will take time. This is why I’ll use step two:

- I’ll use a strategy I’ve seen referenced several times in several different versions. The basic idea is to make letting go less painful by doing it in stages. When we de-clutter we will inevitably find something in the back of our closet that lights up memories. Suddenly we remember why we bought it. Or we reminisce about old times. I have already experienced this first hand. So to make the process more tolerable we can introduce a state between owning and not owning. A timeout where things can wait until we are ready to part ways. The more extreme version of this strategy is to pack everything up in boxes and slowly take out what I need over the next few weeks. Everything that remains in the boxes is stuff I don’t need. A more relaxed version is to use the boxes for “maybe” items. I can then go through my belongings and sort them into three categories: remove, maybe, and keep. In both versions I will come back to the boxes in the future and getting rid of what is still inside should be easier as I now have clear proof that I don’t need the items (at least that is the theory).

- I’m picking up The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up: The Japanese Art of Decluttering and Organizing by Marie Kondō from the library when I come home. I’ve heard it has some tips and tricks.

Money

I stumbled upon this topic while reading about minimalism. And I’m so glad I did as it may turn out to be the most important discovery I have made these last few days months. So a big thanks to Alice Crady for her post on professional freedom. It sparked my interest. And it lead me to Your Money or Your Life and to a review of that book by none other than Mr. Money Mustache.2

The topic I discovered wasn’t just money. I have known about that since I was old enough to browse toy store catalogs. No, what I discovered was a different way of thinking about money. Or, more correctly—I discovered there are people actually thinking about how they spend their money.

I had heard about financial freedom/independence/early retirement/FIRE before. But like most people I had dismissed it as a fringe movement and a pipe dream. Not for me.

But after reading up on it I no longer feel that way.

As I read about these ideas I was struck by how much they are backed up by science and math. This isn’t snake oil salesmanship or wild ideas with no footing. This is simply a rational way to think about spending and saving money. Along with a philosophy of life. And as the penny dropped I realized that my own ideas and beliefs about money were the crazy ones. My attitude towards money—largely shaped by society—was the one out of touch with reality.

In the following I’ll briefly explain what financial freedom is and why I think it makes sense. Then I’ll mention a few steps I’m taking to get started on this journey.

The Financial Freedom Idea

Having financial freedom simply means you are not financially constrained. That you do not depend on your next paycheck and that your budget does not limit you from doing what you want. The freedom is not binary but more of a scale. At one end you don’t have any freedom to maneuver—your budget is severely limiting you and you depend on your next paycheck to make ends meet. At the other end you can do whatever you want and never think about the financial side of things.

Defining financial freedom is simple enough. But the broader financial freedom idea (or FIRE movement) is more than just this. Is a set of beliefs about how to improve your relationship with money, income, and expenses. It is a lifestyle.

The Financial Independence, Retire Early (FIRE) lifestyle is about gaining financial independence and retiring once that is reached. The goal is to retire much earlier than usual. And the way to do this is by saving a much higher percentage of your income and investing those savings.3

But a lifestyle is more than just saving 50%+ of your income and investing that in index funds. As I learned more it quickly became apparent that the FIRE ideas are indeed more holistic. I can recommend Getting Rich: from Zero to Hero in One Blog Post, Manifesto and Can I retire young? for a feel of what this lifestyle is about. I should note that these are just some ideas from two bloggers and there are likely many other views. This is just what I stumbled upon that connected with me.

Why It Makes Sense

To me financial freedom makes sense because the arguments in favor of it are based on scientific evidence, mathematics, and a philosophy I can get behind.

My belief systems regarding money were—and still are—fussy and without much grounding. I save a small percentage of my income, donate an even smaller percentage, and spend the rest on a whim.

It is quite humbling to realize how little I understand my own beliefs about money. More troubling that I don’t agree with these beliefs, yet I still carry them around—and have done so for a long time. Money is everywhere in our modern world, touching every aspect of my life. So my lack of understanding is quite alarming, yet I fear very normal.

Reading about financial freedom is uplifting as I understand and agree with the beliefs this idea proposes. And I understand the reasoning behind these beliefs. Sure, retiring in ten years sounds great. But understanding my own attitude towards and beliefs about money may be a lesson much more valuable than early retirement.

The Science Checks Out

We are diving in the deep end with this one. Science being science the results and conclusions are never straightforward or certain. So to convince myself—and maybe you—I had to do some digging around Wikipedia, Investopedia, world reports, scientific papers, and several news stories trying to explain said scientific papers.

Hedonic Adaptation

Let’s start with Wikipedia for this one:

“The hedonic treadmill, also known as hedonic adaptation, is the observed tendency of humans to quickly return to a relatively stable level of happiness despite major positive or negative events or life changes.” - Hedonic treadmill, Wikipedia

This theory suggests that we return to some (more or less stable, depending on who you ask) happiness set point. Even after major positive or negative life events.

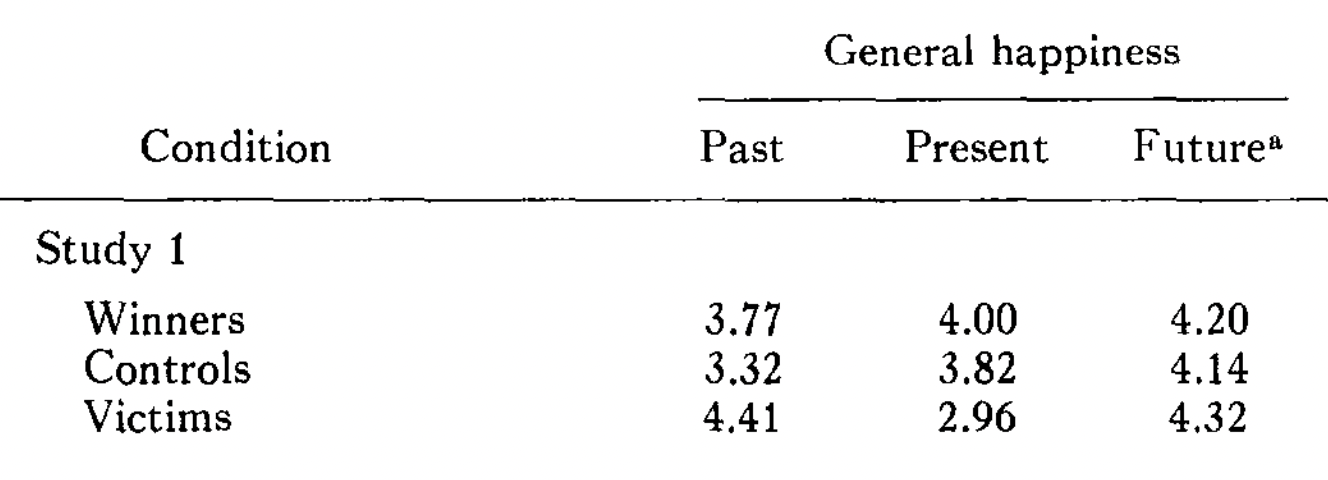

One often cited source is the 1978 paper Lottery Winners and Accident Victims: Is Happiness Relative? by Brickman, Coates, and Janoff-Bulman. In one of the first studies of hedonic adaptation, it showed that people in a control group rated themselves as happy as a group of lottery winners in the past, present, and future. It also suggested that paraplegics expected to be as happy as the lottery winners in a couple of years. I.e., both groups would return to their baseline happiness. Which goes against everything we believe. Lottery winners are supposed to be happy. Happier than the control group. At the very least they should expect to be happier than newly paralyzed victims.4 When first learning about this the normal response is disbelief—this can’t be true?

It turns out there seems to be something about it. There are however lots of wrinkles to this. Some studies show hedonic adaptation, some do not. Some show a static set point for happiness, others show it may change over a lifetime. Some suggest we can control around 40% of our happiness. The rest is determined by our set point (50%) and external circumstances (10%). The whole concept of a single happiness set point may also be too simple as happiness is composed of multiple well-being variables.

Based on the article Beyond the Hedonic Treadmill: Revising the Adaptation Theory of Well-Being, the original hedonic adaptation theory has some flaws and the empirical support for hedonic adaptation in the 1978 paper is mixed. But the authors still fully believe adaptation is an important concept in psychology:

“Although recent studies have challenged the idea that adaptation is inevitable, people do adapt to many life events, and they often do so within a relatively short period of time. Thus, adaptation processes can explain why many factors often have only small influences on happiness. People tend to adapt to these conditions over time.”

Hedonic adaptation appears to be a generally accepted theory. We do adapt. Maybe not to everything and maybe it differs from person to person. In some scenarios we adapt completely, in others only partially. There are many small unknowns. But generally we adapt to changes in our lives rather quickly. This means getting the new phone, a fancy new car, or a bigger house may not improve our happiness much—if any. At least not in the long run. Most likely it won’t.

But adaptation can also work the other way. It may reduce our happiness when reaching financial freedom. Quitting the 9-to-5 may feel great but soon retirement becomes the new normal. One argument against this is the paper Explaining happiness by economist Richard A. Easterlin. In it he argues that hedonic adaptation may not be equal across all domains. In particular he studied the impact of material wealth, marriage, and health in relation to happiness. And it appears that adaptation is more complete for the material domain than it is for the domain of family and health:

Hedonic adaptation, as we have seen, is less complete with regard to family circumstances and health than in the material goods domain. - Explaining happiness

Easterlin shows that as we acquire more material goods, our desire increases in tandem. Once we have a big house and car, we now desire a swimming pool too—something we did not desire before. This behavior is not observed in the domain of health and family and may explain why adaptation is more strongly observed in the material world, including income.

In particular, people make decisions assuming that more income, comfort, and positional goods will make them happier, failing to recognize that hedonic adaptation and social comparison[5] will come into play, raise their aspirations to about the same extent as their actual gains, and leave them feeling no happier than before. As a result, most individuals spend a disproportionate amount of their lives working to make money, and sacrifice family life and health, domains in which aspirations remain fairly constant as actual circumstances change, and where the attainment of one’s goals has a more lasting impact on happiness. Hence, a reallocation of time in favor of family life and health would, on average, increase individual happiness. - Explaining happiness

If we want to maximize our happiness, we should work on domains where hedonic adaptation isn’t as complete. And it appears that we should reduce our focus on income, comfort, and material goods. That sounds very much in line with the financially independent lifestyle. We can reduce our spending without reducing our happiness much—if any—and instead focus our time on more important areas such as family and health.6

Diminishing Marginal Utility

More is not always better. One car may significantly improve your situation. You may depend on it to get to work, pick up kids and groceries, etc. Two cars may also provide some additional value for a family. Three cars? Twenty? Not so much. That is the law of diminishing marginal utility.

“Diminishing marginal utility refers to the phenomenon that each additional unit of gain leads to an ever-smaller increase in subjective value. For example, three bites of candy are better than two bites, but the twentieth bite does not add much to the experience beyond the nineteenth (and could even make it worse). This effect is so well established that it is referred to as the “law of diminishing marginal utility” in economics (Gossen, 1854/1983)” - E.T. Berkman, … J.L. Livingston, in Self-Regulation and Ego Control, 2016

And studies have indeed observed and confirmed this law in relation to income:

“We have thus confirmed the (cardinalist) assumption of nineteenth century economists that marginal utility of income declines with income.” - The Marginal Utility of Income (pdf)

The implications of this law as it relates to money are straightforward. More money won’t continue to provide as much value. More space in your house won’t either. There are diminishing returns on almost anything. So continuing to chase bigger and better just isn’t worth it.

But free time also has diminishing returns. Working five days a week means we cherish the two days off. If we work zero days, the additional five days off may not feel as valuable as our weekends previously did.

The law of diminishing marginal utility more or less suggests that we should live a balanced life.7 At least if we want to maximize utility. Are you living a balanced life right now? I’m not. I spend most of my week working to earn more money although my utility of income is rapidly declining.

The law does not suggest that financial freedom is the way forward. But it does show that excess is bad. The more time or money we have, the less we value any gain of it. My current operating mode of working five days a week to buy things I don’t need sounds stupid with this view.

Income and Happiness

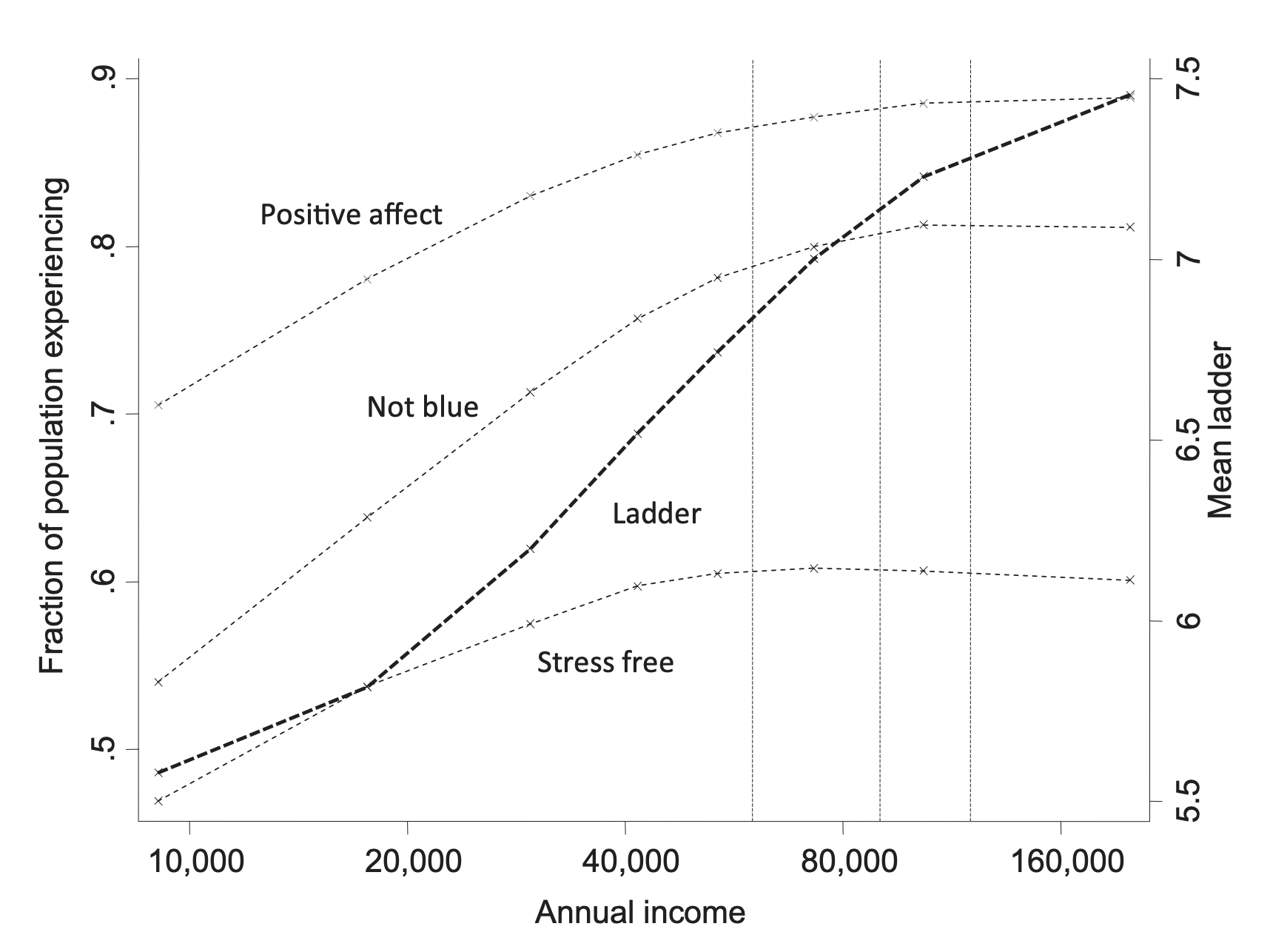

The big one. Going directly after the main question: does higher income equal more happiness? If by happiness you mean evaluation of life, then yes. If you mean emotional well-being the answer is a maybe.

Life evaluation is your general, overall view of life. How satisfied are you? It is the thoughts you have about your life when you stop up and think about it. A way to measure this is with the following question:

“Please imagine a ladder with steps numbered from 0 at the bottom to 10 at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you, and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time?” - High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being

Emotional well-being is the emotional quality of your everyday life. How frequently and how intensely do you feel joy, stress, sadness, anger, and affection. It can be measured with a question about those feelings:

“Did you experience the following feelings during a lot of the day yesterday? How about _____?” - High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being

Using these two measures, Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton studied whether money buys happiness. And their conclusion in 2010 was that:

“…high income buys life satisfaction but not happiness, and that low income is associated both with low life evaluation and low emotional well-being.”

Emotional well-being stops rising at an annual income of ~$75,000, according to their study. However, a new study published by Matthew A. Killingsworth in 2021 suggests that this plateau may not exist and that emotional well-being continues to increase beyond ~$75,000.8

Just Happiness

So, money does buy happiness.

But let’s dig a bit deeper. How do these findings relate to our observations about hedonic adaptation and the law of diminishing marginal utility?

At first glimpse they may seem to contradict each other. But that is not the case. The paper by Kahneman and Deaton directly mentions adaptation as something to be aware of when studying changes in income. If people did not adapt, we would expect much bigger differences in happiness across income levels. But the results do suggest that household income matters for both emotional well-being and life satisfaction—so people do not adapt completely.

The law of diminishing marginal utility is also present in the studies. Both papers use a log scale for income when plotting and correlating. If your income is $20,000 you may take one step up the ladder of life satisfaction with an additional $20,000. But if your income is $40,000 you will need another $40,000 to take a step. You can see this play out in the graph from High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being:

So the studies do not contradict our previous findings. But they do suggest that income buys happiness. At least to a certain point. That is good news as I currently spend a large part of my waking hours trading time for money. At least that isn’t completely wasted.

But asking whether money buys happiness may not be the correct question. Household income may correlate with happiness, but what if something else has a much stronger correlation? Money may buy a bit of happiness, but has science looked at other factors? Instead of asking if money buys happiness, what about the most important factors for a good life?

This amazing 75-year long study on happiness has a suggestion:9

“…the lessons aren’t about wealth or fame or working harder and harder. The clearest message that we get from this 75-year study is this: Good relationships keep us happier and healthier. Period.”

Not money. Not fame. Not working harder. Relationships. And to form good relationships we don’t need much money. What we need is time.

Explaining happiness also suggests that we should focus on domains where hedonic adaptation is less complete. Areas such as family and health are more important than income, comfort, and material goods.

Finally, the World Happiness Report 2012.10 The first entry suggested by Google Scholar for the search term “happiness” and cited by 2515.11

The following table from Appendix B shows the “Effects on life evaluation of each factor, as a multiple of the effect of a 30% increase in income” (reordered most positive to negative):

| Factor | Effect |

|---|---|

| Social support (10% point extra saying yes) | + 4.5 |

| Freedom (10% point extra saying yes) | + 2.1 |

| Corruption (10% point extra saying yes) | + 1.9 |

| Female (versus male) | + 1.5 |

| Unemployment rate (10% point increase) | - 1.3 |

| Single (versus married) | - 2.2 |

| Widowed (versus married) | - 2.9 |

| Separated (versus married) | - 4.0 |

| Individual unemployment (versus employment) | - 6.0 |

| Malaise 8 years earlier (1 standard deviation worse) | - 10.0 |

| Physical health (Poor versus good, self-assessed) | - 15.0 |

The table does not claim to include all important factors for life evaluation. But it does show that a lot of factors are more important than a 30% increase in income. It also suggests—as we have now seen several times—that health, family life, and social support (good relationships) matters more than income.

One thing to note is that unemployment has a significant negative effect on life evaluation. This makes sense as employment is more than just income for most people. Some benefits suggested by the report are: structure to everyday life, shared experiences with colleagues, goals and a purpose, personal status and identity, and enforcement of activity.

Unemployment—especially unwanted—removes all of these benefits. But financial freedom does not require you to quit your job. It may be a big selling point of FIRE, but it is not a requirement for the lifestyle. It is perfectly legal to be financially free and employed. And if that is not desired it is possible to find the same benefits elsewhere. E.g., as a volunteer or with community work.

The Math Checks Out

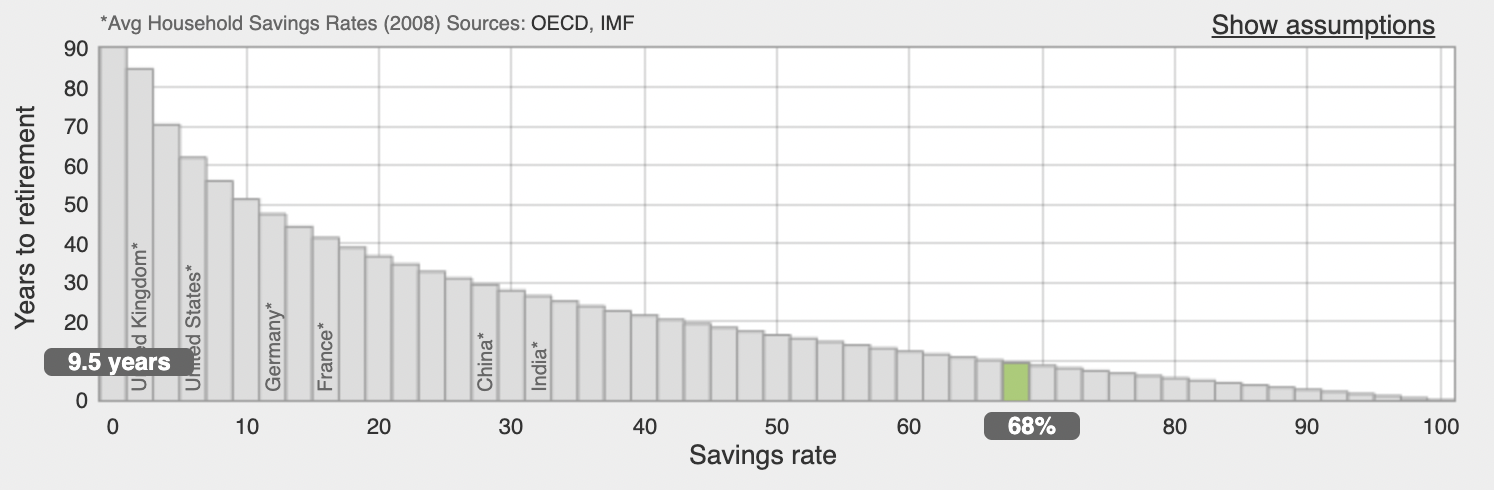

Quickly gaining financial independence boils down to one thing: your savings rate. Everything else is secondary to this number. Your income, current worth, return on investment, and any other metric you can think of are all less important.

Let’s start with a few simple observations from Wikipedia:

- At a savings rate of 10%, it takes (1-0.1)/0.1 = 9 years of work to save for 1 year of living expenses.

- At a savings rate of 25%, it takes (1-0.25)/0.25 = 3 years of work to save for 1 year of living expenses.

- At a savings rate of 50%, it takes (1-0.5)/0.5 = 1 year of work to save for 1 year of living expenses.

- At a savings rate of 75%, it takes (1-0.75)/0.75 = 1/3 year = 4 months of work to save for 1 year of living expenses.

So if you save 10% you will have to work 9 years to save for 1. But if you save 75% you only need 4 months.

But what if I already have $1 million in the bank? The most important metric is still your savings rate. If you won that money in a lottery, quit your job, and your annual spending is now $1 million you’ll be out on the street in roughly one year. Your total wealth or income does not matter. What matters is the relationship between your income, portfolio, and expenses.

Next up we need to estimate how much we should save to retire safely. Several factors are at play here, such as risk tolerance, expected spending during retirement, flexibility, etc. This means the size of the nest egg for retirement is somewhat down to personal preferences. With that said there are still some overall suggestions based on historical data.

A general guideline is the 4% rule which is based on a study often referred to as the Trinity Study (a 1998 paper by three professors at Trinity University). The rule suggests that 4% can be used as a rough guideline for a safe withdrawal rate. This 4% is based on the initial portfolio value at the start of retirement. So whatever value your portfolio has, 4% of that is your annual budget in dollars. This is a useful way to think about retirement portfolio value as we can estimate the required size based on our current expenses. We just need a portfolio big enough that 4% of it covers our annual spending.

Note that this 4% guideline is used to compute our withdrawal amount in dollars (or whatever currency you use). It does not mean that we withdraw 4% from the portfolio every year. The 4% is based on the starting point. Some years we may withdraw what amounts to more than 4% and some years less. If we start with a portfolio of $1000 we can withdraw $40 every year to cover our expenses. In most scenarios we would want this dollar amount to increase with the rate of inflation. $40 in 30 years can most likely buy me a lot less than it can today. So to keep the same living standard the dollar amount to withdraw will follow inflation.

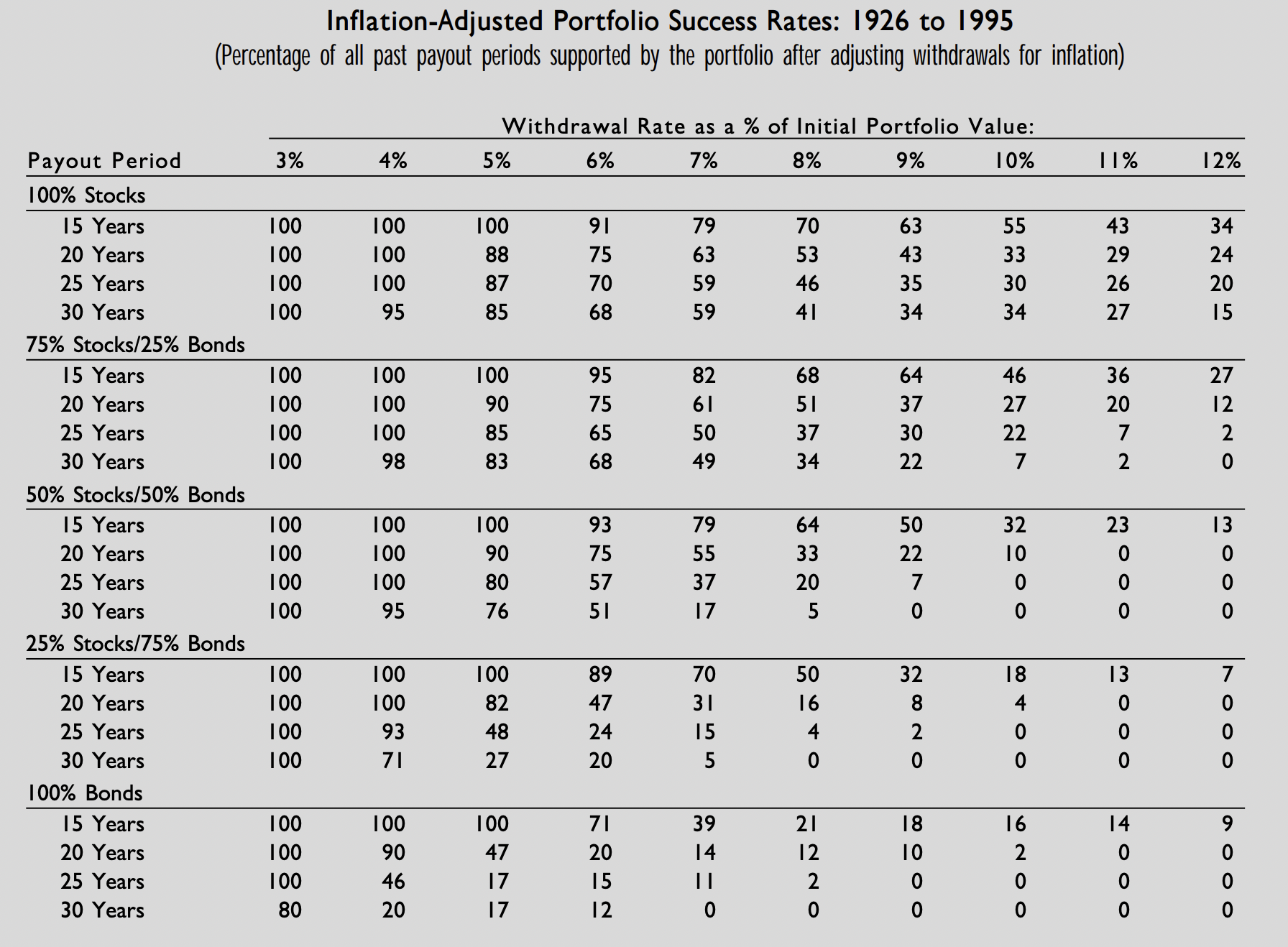

According to the Trinity Study, a 4% withdrawal rate keeping up with inflation has a very low failure rate. Using historical data from 1926 to 1995, the study shows a retiree would be able to withdraw for 30 years with a low risk of exhausting the entire portfolio and thereby running out of money. For a 100% stock-based portfolio the success rate was 95% and for a 75/25 stock/bond portfolio it was 98%. For a 50/50 portfolio the success rate was also 95%.

The Trinity Study suggests 4%. But it is by no means a guarantee. High success rate does not mean guaranteed success. There was a risk the portfolio would deplete earlier than 30 years. Furthermore, there are differences between the study and the FIRE movement. One big one being a much longer expected retirement duration. Another one is that we are now in 2021. This all means that the 4% rule is a debated topic. This post explains why Mr. Money Mustache uses the 4% rule and this series by Early Retirement Now has a lot of good information arguing against blindly following it.

I’m not going to argue for or against the rule. There are already much smarter people doing that and I suggest you read some of their arguments. To some extent it comes down to personal preferences, especially risk aversion.12 But to have a starting point I’ll use 4% in the following calculations. The same principles apply to a 3.5%, 3%, or any other withdrawal rate. The time horizon will simply be longer for smaller rates and shorter for larger ones.13

Using the 4% rule we can now calculate how big we need our portfolio to be before we can retire.

What we want is:

retirement portfolio * 4% = annual spendingAs this means we can satisfy our annual spending with 4% of our portfolio.

So to get our retirement portfolio value:

retirement portfolio = annual spending / 4%And as dividing by 4% is the same as multiplying by 25 (4% = 4/100 = 1/25) we get:

retirement portfolio = annual spending * 25If we have 25 times our annual spending in our portfolio we see that a 4% withdrawal gives us enough money to satisfy your annual spending:

annual spending * 25 * 4% = annual spendingLet’s say our annual spending is 100. We can see that:

100 * 25 * 4% = 2500 * 4% = 100If we save 2500 we get to withdraw 100 under the 4% rule. So 2500 would be enough to satisfy our spending using a 4% withdrawal strategy.

You don’t need to remember all of this. The important point is that withdrawal rate, retirement portfolio value, and annual spending are linked together and using the withdrawal rate you can easily compute your retirement portfolio requirements. For 4% you need 25 times your annual spending. For 3.5% you need 28.6 times and for 3% you need 33.33. For 5% you only need 20x.14

If we go back to the observations on savings rate from before:

- At a savings rate of 10%, it takes (1-0.1)/0.1 = 9 years of work to save for 1 year of living expenses.

- At a savings rate of 25%, it takes (1-0.25)/0.25 = 3 years of work to save for 1 year of living expenses.

- At a savings rate of 50%, it takes (1-0.5)/0.5 = 1 year of work to save for 1 year of living expenses.

- At a savings rate of 75%, it takes (1-0.75)/0.75 = 1/3 year = 4 months of work to save for 1 year of living expenses.

And we use our 25 portfolio multiplier from the 4% rule we get:

- At a savings rate of 10%, it takes ((1-0.1)/0.1)*25 = 225 years to retire.

- At a savings rate of 25%, it takes ((1-0.25)/0.25)*25 = 75 years to retire.

- At a savings rate of 50%, it takes (((1-0.5)/0.5)*25 = 25 years to retire.

- At a savings rate of 75%, it takes ((1-0.75)/0.75)*25 = 8 years and 4 months to retire.

At this point it should be quite clear how much of an impact the savings rate has. But you may also suspect the numbers are a bit off. A common savings rate suggestion in the general population is around 20%. But with that it would take more than 75 years to retire using these calculations. And while we work most of our lives, few of us expect to work 75 years.

What we are missing is the fact that over the savings period, be it 225 years or 8, we have another factor to consider—time. And using time to our advantage we can make our money work for us. We can invest and reap the benefits of compounding. But before we consider the implications of time, let’s just look at the numbers once more and observe that even without investing a single dollar, it is possible to save enough for retirement in less than 9 years.15 In fact, Jacob Lund Fisker from Early Retirement Extreme notes that for extreme savers, compounding is not what will grant them financial independence:

There is simply not enough time for compounding to make much of a difference. Instead compounding becomes somewhat irrelevant as the eventual portfolio becomes more focused on preserving principal, generating income, and not suffering too much in terms of inflation and taxes. - How I became financially independent in 5 years

While compounding does not matter as much for extreme savers, it will for most of us. I don’t expect to be financially independent in 5 years. And even if I did, I would have to maintain my portfolio for a long time to stay independent. So let’s talk about time.

The two opposing forces we’ll meet are inflation and return on investment (ROI). Inflation reduces the value of our money by increasing prices. Yesterday a banana was $1. Today it is $2. Big-time inflation and I can suddenly only afford half of the bananas I could yesterday. Return of investment is what we expect to get when we invest our money. We can invest in companies and thereby receive returns from future profits. Or we can invest in a house and rent it out. Or we can speculate in gold, bitcoin, or pretty much anything at this point.16 The point is to grow our portfolio in some way without working too much to do so.

Inflation and investing are powerful forces and much more complicated than this. But I don’t have a degree in Economics and I don’t expect you have one either. So I’ll keep it more or less at this level. I do think it is valuable to learn more about economics but you’ll have to do so elsewhere.

So. Inflation and ROI. Let’s do some back-of-the-envelope calculations.

The average inflation measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) from 1957 to 2018 was 3.8%.17 And the average annual return for S&P500 in the same period was 8%.

Computing the Inflation-adjusted return:

Inflation-adjusted return = (1 + Stock Return) / (1 + Inflation) - 1Inflation-adjusted return = (1 + 0.08) / (1 + 0.038) - 1 = 0.0405Voila! Based on these historic numbers we see that our portfolio would grow on average 4% every year, adjusted for inflation. Exactly the rate at which we would withdraw (4%) leaving our portfolio intact even as we subtract money from it to cover our annual expenses. The actual historical average annual return, adjusted for inflation, is around 7% for the S&P500 according to Investopedia and 6.12% annualized return according to moneychimp. Quite a bit better than our back-of-the-envelope 4%.18

We are almost ready to go back to our running time-to-retirement question. This time with a bit more realistic numbers. But we are still missing one final factor—taxes. Unfortunately, as I have discovered while diving into this topic, taxes can be mind-boggling complex. Right now I’m in the process of reading a 57-page guide on how to understand taxes on investments in my country. And that just covers some of the very basic information I need to fill out my yearly tax form.

To come up with a tax estimate that covers most people is impossible. Instead I’ll simply use ~ 33% and if your country differs vastly from mine you’ll have to substitute with your tax estimate in the following. Fortunately we are almost done with the manual calculations.

We now have back-of-the-envelope estimates for how time impacts our money when invested. Including inflation, returns, and taxes. Let’s get back to our time-to-retirement scenario. Not accounting for time we had:

- At a savings rate of 10%, it takes ((1-0.1)/0.1)*25 = 225 years to retire.

- At a savings rate of 25%, it takes ((1-0.25)/0.25)*25 = 75 years to retire.

- At a savings rate of 50%, it takes (((1-0.5)/0.5)*25 = 25 years to retire.

- At a savings rate of 75%, it takes ((1-0.75)/0.75)*25 = 8 years and 4 months to retire.

With a 4% return after inflation and tax (6% return after inflation and 33% tax gives us a nice round number) we get the following:

- At a savings rate of 10%, it takes 58.7 years to retire.

- At a savings rate of 25%, it takes 35.3 years to retire.

- At a savings rate of 50%, it takes 17.7 years to retire.

- At a savings rate of 75%, it takes 7.3 years to retire.

To illustrate the impact of savings rate versus return, let’s use 8% return after inflation and see how that differs:

- At a savings rate of 10%, it takes 49.4 years to retire.

- At a savings rate of 25%, it takes 31 years to retire.

- At a savings rate of 50%, it takes 16.3 years to retire.

- At a savings rate of 75%, it takes 7.1 years to retire.

A two percentage point difference in return after inflation would mean a lot at lower savings rates. In the 10%-25% range you would shave off 4.3 to 9.3 years. Retiring almost 10 years earlier is a big deal so the return does indeed matter. But then look at the higher end. Not so much here. Only 0.2 to 1.4 years.

What if we change up the withdrawal rate?

3% withdrawal rate, 6% return after inflation:

- At a savings rate of 10%, it takes 65.4 years to retire.

- At a savings rate of 25%, it takes 41 years to retire.

- At a savings rate of 50%, it takes 21.6 years to retire.

- At a savings rate of 75%, it takes 9.4 years to retire.

These numbers are simply bigger as we need a larger portfolio to cover our expenses if we only allow ourselves to withdraw 3% instead of 4%.

These examples hopefully demonstrate the point I opened this whole section with. That savings rate thumps everything else when it comes to quick financial freedom. We have tried changing the different numbers and accounted for most variables (although only very basic back-of-the-envelope calculations). But changing these numbers does not make nearly as much of a difference as the savings rate does.

If you save 25% of your income and you increase your ROI by 1/3 you go from 35.3 years to retirement to 31. A 4.3-year difference. If you instead increase your savings rate by 1/3 to 33% you now only have 28.3 years to retirement. A 7-year difference. And as your savings rate increases that difference becomes even bigger. At a 50% savings rate you shave off 1.4 years by increasing the ROI but 7.1 years by increasing the savings rate to 66%.

Of course increasing the ROI often sounds more appealing as that does not require us to change our lifestyle. It just requires us to be smarter about our investments. But investing is hard and any increase in ROI often comes with a similar increase in risk. This section deals with the math but we have already seen that reducing our spending may not be as bad as we think. The science section showed us that. And as we will soon see in the philosophy section it may even be desirable.

I have used this tool to compute the final scenarios. I suggest you play around with it a bit. It gives you a good feel for how the different metrics influence your time-to-retirement. Also, on the graph you can see that the fun begins at the higher savings rates and that each percentage point matters quite a bit.

There we have it.

Pick a savings rate and watch the portfolio grow as your time towards retirement goes to zero. We can now live happily ever after. Withdrawing 4% every year without a worry in the world that our portfolio will ever deplete as the math shows it won’t. It may even increase by 2-3% year after year!

Of course, as I have hinted at several times, it may will not be that easy.

I’m just learning about all of this so I don’t know the pitfalls and traps that lie ahead either. But despite this the arguments and math above has convinced me that:

- Shaving many years of time-to-retirement is indeed possible.

- The way to do that is by saving a lot more than the norm.

In short, the savings rate is what I will focus on. And as I continue to learn I can improve my returns, tax, fees, and all the other stuff I don’t even know to improve yet.

The Philosophy Checks Out

Financial freedom is mostly about spending less money. Not about earning more. This means a smaller footprint on the world which is good for the environment.

It also ties in with ideas from Minimalism. That less is more. That being intentional with money is a good thing. That we don’t need much and that happiness does not come from acquiring more.

Financial freedom is about living differently, not about downgrading. Science has already shown that money isn’t the best way to chase happiness. There are other paths. And financial freedom is about exploring these. Instead of trading time for money, invest that time in relationships, health, creative outlets, nature, simple things, or whatever interests you.

Financial freedom is about realizing that comfort won’t make a good life. Bigger house, better car. Luxury hotels and A/C environments. This isn’t the stuff of happiness. It’s comfort and nothing more. And comfort is the enemy. You shouldn’t seek out comfort. You should be wary of it.

Another way to put this into perspective is this post which I found quite interesting. The premise is that most of what we want to buy is for convenience. I want a new lightweight tripod for my camera as the one I have is too heavy. Clearly this investment would be for convenience. (Interestingly enough I did not think of it that way before. Instead I fell for clever marketing.) But convenience does not make us happy. Hedonic adaptation shows us that.

More illustrative—and useful as a tool—is the thought experiment Mr. Money Mustache makes: take whatever convenience you desire and dial it up to the extreme. Instead of a lightweight tripod, why not a completely weightless tripod? Or even better, an entire film crew to carry all my gear. Now that would be convenient. Would it make me happier? Nope.

The mockery shows that convenience isn’t happiness. Convenience may improve our lives, but only to a certain point. In many cases it may even make life worse. And yet we often throw our money after things to make life more convenient. If convenience was so great we’d all be spending all of our free time laying on the couch doing nothing. And we’d be happy. But we are not.

Unfortunately it is not always easy to see this mistake when we want something. I didn’t see it with the tripod. And I have many other things I want but am not sure about. I found the technique used by Mr. Money Mustache quite helpful thinking about this and maybe you will too. Convincing us that we need more is big business so we need all the tools and help we can get.

Finally, financial freedom also pairs well with Stoicism.

How I’m Getting Started

Commit to Save a Percentage of My Income Each Month

This is basically what it comes down to. Save a large percentage of your income and put that money to work by investing it. I want to start with at least 50% and hopefully increase that percentage as I learn and adopt this new lifestyle. As the math showed, the savings rate is the most important factor and just a few percentage points can make a big difference.

I recognize this will not be easy. It is a big lifestyle change and I have lots to learn. So rather than setting the bar too high and immediately failing I will see how 50% goes and move from there. (Even 50% may be a high bar to clear. But I want a challenging goal that excites me. And I think 50% hits that mark.)

Start Tracking My Expenses

Right now I’m walking blindfolded. I don’t know what I spend my money on so I have no idea what or where I can reduce my spending. I’ve made a list of things I can immediately unsubscribe from and bad habits I can work on. But other than that I simply don’t know.

So my first action should be learning to see. I need to start tracking all my expenses so I know what I am spending money on. There seem to be some apps and services that can help do this but from what I have gathered they work mostly in the US. So I will go with a simple spreadsheet. In some way I think this makes more sense than using a third party service. The goal is to make my spending habits so simple that they are easy to track.

Financial Freedom ≠ Early Retirement

I don’t know if I want early retirement. Or how soon. I don’t even know if it is possible with the lifestyle I desire. But that does not mean I can’t build more financial freedom and stability. Right now I need a paycheck every month. I have some savings but if I suddenly stopped receiving monthly income from my job I would not last too long with my current lifestyle (social security is great in my country so I would not suffer). This fact means that I do not have much financial freedom or stability. I do have some. More than I would have with no savings at all. But I still depend on my job. I want to build more financial freedom so I can depend less and less on a full-time job trading time for money.

Curiosity

During my two think weeks I read a lot of stuff that was not directly related to any of the topics I had set out to study. I read about artificial intelligence, blockchain, biohacking, github pages, a climbing trip report from Kyrgyzstan (related video), and much more. I also brainstormed a whole bunch of small projects I would love to do.

But then I felt bad. I was using (wasting) my time on topics that were not on the list I set out to explore. And here’s something you should know about me—I only function when everything fits into the bigger picture. If I’m working on a project or reading about something, I need to be able to explain myself why. And usually I solve that by putting all activities into categories. If I’m running I’m doing it for my health, fitness, and often to clear my head. If I’m journaling in the morning I’m doing it for personal growth. When I’m going to work I do it for money and fulfillment.

And now I had all these different categories that did not fit into my bigger picture. I’m not going to write or create videos about blockchain technology. And I’m not going to develop anything using it either. So why bother?

Because something inside me wanted to. And that something was curiosity.

As I thought more about my conflicting feelings I realized what was driving me. I was curious about artificial intelligence and blockchain technology, even if I knew that I would not use that knowledge for anything specific.

I now had my category. Curiosity. I could put smaller topics and projects under this umbrella and it would silence the voice telling me I was wasting my time. My next question—was curiosity worth pursuing?

Turns out the answer is yes. Big yes.

The Benefits of Curiosity

The series Why Curiosity Matters explains a lot of the benefits of curiosity. Although it is focused on curiosity in the workplace I found it interesting. When we are curious we are less prone to confirmation bias and stereotyping, we are more creative and more likely to make constructive suggestions. Curiosity reduces group conflict and makes for more open communication where people share and listen.

These are just some of the benefits mentioned in the curiosity series. But as I started thinking about curiosity I quickly realized it was everywhere.

I have been practicing curiosity for years with the books I read. My topics are all over the place and I never feel guilty picking up a book unrelated to anything I do. I feel good about that. Excited. And I have anecdotal evidence that it is indeed beneficial. Books inspire, motivate, challenge, and inform me (and much more).

The Artist’s Way describes a method called The Artist Date that creatives can use to help fill up their inner creative wells. A date for you and your inner artist. Time set aside to do whatever we want, no strings attached. If this isn’t a call for curiosity I don’t know what is. Simply set time aside to be curious and soon you will see your creativity improve (and as we have learned, this theory is indeed backed by science).

I was also reminded of a recent Rich Roll podcast that had a short section about curiosity. This view was a much broader appreciation for curiosity. Not just as a simple tool to boost creativity or make office workers more profitable for corporations. Curiosity is more than that. So much so that I feel embarrassed to have questioned it. Curiosity is what makes life interesting. Makes it worth living even. There are so many wonders in this world. So many things to be awed by. But to experience any of this we need to be open and prepared to receive. We need to give ourselves permission to look around and ask why.

How to Spark My Curiosity

My issue with curiosity wasn’t so much that I wasn’t curious. It was that I did not feel good about leaning into this curiosity. I know now better. But knowledge is rarely enough. When I come home to a busy everyday life I will most likely kick curiosity to the curb (again) and not think twice about it.

So here are some things I will focus on:

- Stay curious about the books I read. This is an area where I’m doing well. I read whatever I find interesting and have no issue with that.

- Be curious online. Whenever I find something interesting I often save it to my Pocket. That is one piece of the puzzle. But I also need to give myself permission to browse through my list and read the things I save.

- Be curious at work. Ask questions. Sometimes I’m curious but at times I also put my head down and work on what is in front of me. Being focused is good but I also want to stay curious. It will benefit me in the long run.

- Set time aside for simple curiosity. I did this the last two weeks and it was amazing.

Create

Over the last 3 years I have published 71 videos to YouTube. I like that. I love creating these and I can see progress from my first videos to my latest ones. I still have a (very) long way to go but I’m ready to make videos for someone other than myself. At least I’m ready to try.

I have a personal mantra for my video creation process. “I want to create something that makes me proud.” Whenever I’m in despair or feel pulled towards other motives (money, popularity, ego), I come back to this. It has helped me a great deal and motivated me to continue learning and producing even though I know most likely nobody will watch the hours of video I have created.

I have enjoyed creating videos for myself. But creative work is to be shared. I’ll never make a change in the world if nobody sees what I create.

Seth Godin’s book The Practice: Shipping Creative Work is mainly what influenced this new view. In the book, Seth shows that sharing your work is the generous thing to do. At least if the work seeks to make a change. If it is something only you could create. Something that improves the world in some small way. Then share it with generosity.

This means I need to be clear about who my work is for. It is never for everybody. And I need to actively seek out these people, these communities, and ask them to consider my work. To help and to learn from the feedback. If the feedback is crickets that’s a sign too.

I know one pitfall (of many) to pay special attention to. I must be careful not to mistake this for popularity. I have been in that pit before. Not that I have been popular. But I have tried and it drained all joy I had creating. I want to create and I want to share. But for the right reasons.

Moving Forward

I want to share the work I do. And that means finding my audience and creating for them. To do that I need to include a few new steps in my process. For each new video/blog post I will (try to):

- Have a clear idea who it is for

- Have a clear idea what change I seek to make

- Have a clear idea how I will connect with people

Hopefully this will guide me and help me get feedback so I can learn to create for someone other than just myself.

“The path forward is about curiosity, generosity, and connection. These are the three foundations of art.” - Seth Godin in The Practice.

Reading this made me even more excited about curiosity. I have addressed the two first foundations. Now the third:

Relationships and Community

Relationships are essential to a good life. Just see the longest study on happiness for some scientific evidence.

I’m an expert at being alone. Two weeks on my own in a foreign country is nothing to me. Alone in the woods on a cold, dark winter night? Love it. But I also cherish being with other people. I just don’t need it as often. It is not how I build up energy. I do that alone. And when I’m recharged I love to spend that energy with friends and family. In short, I’m an introvert.

I have a few close friendships. I truly value these and want to strengthen them. Same goes for my loving family. It is something I often forget or neglect. It is so easy to take for granted. I don’t want that. I want to be grateful instead.

One area where I lack is community. I’m part of a community at work. And I have a few weak ties to other communities. But that is not a lot. I would love to have more communal experiences. A stronger sense of belonging.

Moving Forward

I believe strengthening relationships and building new ones is all about one thing: investing. Any bond becomes stronger the more we invest in it. We can invest time, energy, money, pain, vulnerability, and all sorts of things in our relationships. And they grow as a result.

Therefore I want to invest in my friendships and family. Some things I want to focus on:

- Reach out and plan things. The first and easiest investment is reaching out and planning something. After that it is almost just showing up and being present. But showing up and being present is harder than it sounds. So this is also worth paying attention to.

- Set time, energy, and money aside. Relationships are only going to grow if I’m prepared to invest in them. Show up depleted and no growth will happen.

- Schedule it in my calendar. A small but important thing. In the past I have not been good at scheduling or planning things. But if I want to balance relationships with all my other goals I need a stronger calendar game.

I also want to invest in new communities. One place to do so online is reddit. A quick search revealed more than 10+ communities I would love to be part of.19 I know some of the bigger communities can be a bit toxic at times. But if I steer clear of that I believe it is possible to find good communal experiences.

Online communities may not provide the full experience that offline communities can offer. But they have other upsides and I still believe being part of an online community can be rewarding. And for someone with a bit of social anxiety it is a lot easier to get started.

I want to connect to offline communities around me as well. It does not have to be anything big at first. A few simple connections and encounters are all I seek to begin with.

The Future

I can’t control the future. But I can control what I focus on. I have sketched out five such areas. They don’t cover everything in my life but they touch what I believe is important—health, relationships, creativity, work, adventure, and philosophy of life.

My task is now to live up to this memo. The best I can. I know I will fall short on many occasions. But I also have what it takes to get back up. I’m excited about the future and I’m already living and breathing the words written on this page.

This is my memo. I hope it inspired you in some way. Now it is your turn. You don’t have to go to Germany for two weeks alone. But you do need to set time aside to think, read, and write without distractions. This isn’t something you can do while Netflix is running in the background. Get away for a bit if possible. Slow down. Then think about what it is you want with your life. Not an easy question. But an important one.

16-29 Oct 2021. Mittenwald, Germany.20

-

Mittenwald is a beautiful small town tucked in between the mountains near the Austrian border. I loved every second being there and can recommend it as a base for hiking trips and other nature adventures. ↩

-

I love the internet. Mr. Money Mustache runs a great blog that I can only recommend. It is one of the main sources that got me interested in this whole thing. ↩

-

Read the Wikipedia entry for FIRE for a good introduction to the main ideas. ↩

-

The lottery winners indeed rated themselves as happier than paralyzed victims in the present. As would be expected. But when rating future happiness the two groups did not differ significantly. Paraplegic victims expected to be as happy as lottery winners. The paper warns that this finding should be “viewed most cautiously” as 10 paraplegics did not want to answer the future happiness question. If their refusal is due to a negative view of the future it may bring down the future happiness evaluation for the paraplegic group. ↩

-

Read “What is Hedonic Adaptation and How Can it Turn You Into a Sucka?” for a more colorful explanation of hedonic adaptation and how it relates to our buying habits. ↩

-

This is my personal interpretation. ↩

-

The Killingsworth paper has several other interesting observations and speculations as to why income is correlated with well-being. Having control over one’s life accounted for 74% of the association between income and experienced well-being. This suggests that control may be related to well-being and that money may buy such control. Another interesting finding was that time poverty increased with income. High-income earners generally felt more rushed than low-income earners. The data also showed that time poverty negatively affected the relationship between income and experienced well-being. High-income households still had higher experienced well-being, but those not in a hurry had a steeper association. ↩

-

The 2012 World Happiness Report is the first of many reports. You can find them all at worldhappiness.report. I have browsed through the later reports but most of them seem to target more specific questions so I have decided to use the information from the 2012 report. I did find another interesting section in the 2017 report called The Key Determinants of Happiness And Misery. A quote from the conclusion suggests that income does matter for happiness but a lot of other factors may be more important: “Even so, household income per head explains under 2% of the variance of happiness in any country. Moreover it is largely relative income that matters, so as countries have become richer, many have failed to experience any increase in their average happiness. ↩

-

Yes. This is largely how I do “research”. Enter something into Google Scholar or just regular old Google and see what pops up. Keep that in mind as you read the rest of my post. ↩

-

While it may come down to personal preferences, it is still a very good idea to be informed and consider the different arguments. You may believe you are okay with the risk involved in e.g., a 5% withdrawal rate. But you can only accurately make this decision if you know what the risks are. A highlight to point out is that we do not need to make the decision now. Most likely we won’t have to make it anytime soon. We can start saving now and retire once we feel comfortable. ↩

-

If you want to play around with different retirement portfolios you can try this simulation tool. ↩

-

The easy way to get your portfolio multiplier is 100 / withdrawal rate number. E.g., 100 / 5 = 20. 100 / 4 = 25. ↩

-

As these numbers do not consider time they don’t take into account inflation either. Time can work in our favor with profitable investments, but it can also work against us if we keep our money under our mattresses. If we assume we can maintain the savings rate while accounting for inflation (prices will increase but so will our salary) and that we invest our money in a way that stays level with inflation, the numbers still hold up. It should be noted that to stay retired we need to invest our money in a way that beats inflation. Otherwise 25 times our annual spending will be gone in 25 years. ↩

-

Not that I recommend doing this. ↩

-

Technically my data is from one of two CPIs reported in the U.S. It is from the CPI for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U). According to Investopedia this accounts for 88% of the U.S. population. The other reported CPI, the CPI for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W) accounts for at least 28% of the population. As the CPI-U best accounts for the general public I’ll use that. ↩

-

This discrepancy should also give you pause. 4% vs 7% is a huge difference and shows our back-of-the-envelope numbers shouldn’t be blindly trusted. Even the different sources don’t agree on a number. Furthermore, the way inflation is measured is also a debated topic and critics argue it may understate the true rate of inflation. ↩

-

My biggest concern is that some reddit communities are too superficial. The study on happiness emphasized strong connections and I’m not sure a site like reddit is built for that. But I’ll give it a try. I also have other online ideas with smaller communities I may try out. ↩

-

I developed all the ideas for this post during my two think weeks. The distraction-free environment and the freedom I had was amazing. I did a large part of the writing during this period too. But refining everything took quite a while so I spent a few weeks after coming home doing this. ↩